Annie Chapman aka Dark Annie, Annie Siffey, Sievey or Sivvey

Born: Annie Eliza Smith in September 1841.

Father: George Smith of Harrow Road. Described on the marriage certificate as a Private, 2nd Battalion of Lifeguards. At the time of his death he was listed as a servant.

Mother: Ruth Chapman of Market Street.

Annie's parents were married on February 22, 1842, 6 months after Annie was born. The marriage took place in Paddington.

She had three sisters, Emily Latitia (b.1844), Georgina (b.1856) and Mirium Ruth (b.1858). A brother, Fountain Smith was born in 1861. The sisters appeared not to get along with Annie.

Description:

- 5' tall

- 47 years old at time of death

- Pallid complexion

- Blue eyes

- Dark brown wavy hair

- Excellent teeth (possibly two missing in lower jaw)

- Strongly built (stout)

- Thick nose

- She was under-nourished and suffering from a chronic disease of the lungs (tuberculosis) and brain tissue. It is said that she was dying (these could also be symptoms of syphilis).

- Although she has a drinking problem she is not described as an alcoholic.

Her friend Amelia Palmer described her as "sober, steady going woman who seldom took any drink." She was, however, known to have a taste for rum.

History:

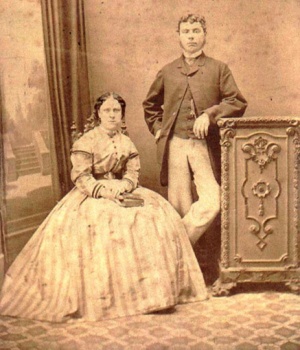

Annie and John Chapman, c.1869

(Chapman family/Neal Shelden)Annie married John Chapman, a coachman, on May 1, 1869. She was 28 at the time of her marriage.

Their residence on the marriage certificate is listed as 29 Montpelier Place, Brompton. This is also where her mother lived until her (mother's) death in 1893. In 1870 they moved to 1 Brook Mews in Bayswater and then in 1873 to 17 South Bruton Mews, Berkeley Square. In 1881 they moved to Windsor where John took a job as a domestic coachman.

The couple had three children. Emily Ruth Chapman, born 1870, Annie Georgina Chapman, born 1873 and John Alfred Chapman, born in 1880. John was a cripple and sent to a home and Emily Ruth died of meningitis at the age of twelve.

Annie and John separated by mutual consent in 1884 or 1885. The reason is uncertain. A police report says it was because of her "drunken and immoral ways." She was arrested several times in Windsor for drunkenness and it is believed her husband was also a heavy drinker.

John Chapman semi-regularly paid his wife 10 shillings per week by Post Office order until his death on Christmas day in 1886. At the time of his death he was living at Grove Road, Windsor. He died of cirrhosis of the liver and dropsy. Annie found out about his death through her brother-in-law who lived in Oxford Street, Whitechapel. On telling Amelia Palmer about it she cried. Palmer said that even two years later she seemed downcast when speaking of her children and how "since the death of her husband she seemed to have given away all together."

Sometime during 1886 she was living with a sieve maker named John Sivvey (unknown whether this is a nickname or not) at the common lodging house at 30 Dorset Street, Spitalfields. He left her soon after her husband's death, probably when the money stopped coming. He moved to Notting Hill.

From May or June 1888, Annie was living consistently at Crossingham's Lodging House at 35 Dorset Street, Spitalfields, which catered for approximately 300 people. The deputy was Timothy Donovan.

More recently, Annie had been having a relationship with Edward Stanley, a bricklayer's mate, known as the Pensioner. At the time of Annie's death he was living at 1 Osborn Place, Whitechapel. He claimed to be a member of the military but later admitted that he was not and was not drawing a pension from any military unit.

Stanley and Annie spent weekends together at Crossingham's. Stanley instructed Donovan to turn Annie away if she tried to enter with another man. He often paid for Annie's bed as well as that of Eliza Cooper. They spent Saturdays and Sundays together, parting between 1:00 and 3:00 AM on Sundays. Stanley said that he had known Annie in Windsor.

Annie didn't take to prostitution until after her husband's death. Prior to that she lived off the allowance he sent her and worked doing crochet-work and selling flowers.

In mid to late August of 1888 she ran into her brother Fountain Smith on Commercial Road. She said she was hard up but would not tell him where she was living. He gave her 2 shillings.

Saturday, September 1, 1888

Edward Stanley returns after having been away since August 6. He meets Annie at the corner of Brushfield Street.

Sometime close to this date, Annie has a fight with Eliza Cooper. The fight has several different tellings but all revolve around Edward Stanley.

An argument breaks out in the Britannia Public House between Eliza Cooper and Annie. Also present are Stanley and Harry the Hawker. Cooper is Annie's rival for the affections of Stanley. Cooper struck her, giving her a black eye and bruising her breast.

The cause is alternately given as:

Chapman noticed Cooper palming a florin belonging to Harry, who was drunk, and replacing it with a penny. Chapman mentions this to Harry and otherwise calls attention to Cooper's deceit. Cooper says she struck Annie in the pub on September 2nd.

Amelia Palmer says that Annie told her the argument took place at the pub but the fisticuffs took place at the lodging house, later.

John Evans, night watchman at the lodging house says the fight broke out in the lodging house on September 6th. Cooper also says that the fight was not over Harry but over soap which Annie had borrowed for the Pensioner and not returned. In one version of the story, Annie is to have thrown a half penny at Cooper and slapped her in the face saying "Think yourself lucky I did not do more."

Donovan states that on August 30th he noticed she had a black eye. "Tim, this is lovely, aint it." She is to have said to him. Stanley noticed that she had a black eye on the evening of September 2nd and on the 3rd Annie showed her bruises to Amelia Palmer.

Donovan will tell the inquest into her death that she was not at the lodging house during the week prior to her death. So it appears from the bulk of the evidence that the fight took place in the last few days of August and probably in the lodging house.

Chapman says that she may have to go to the infirmary but there is no record of any woman being admitted to either Whitechapel or Spitalfields workhouse infirmaries. She may have picked up medication though.

Monday, September 3:

She meets Amelia Palmer in Dorset Street. "How did you get that?" asks Palmer, noticing the bruise on her right temple. By way of answer, Annie opened her dress. "Yes," Annie said "look at my chest." Annie complains of feeling unwell and says she may go see her sister. "If I can get a pair of boots from my sister," she says "I may go hop picking."

Tuesday, September 4:

Amelia Palmer again sees Annie near Christ Church. Chapman again complains she is feeling ill and says she may go the casual ward for a day or two. She says she has had nothing to eat or drink all day. Palmer gives her 2d for tea and warns her not to spend it on rum.

Wednesday-Thursday, September 5-6:

Possibly she is in the casual ward although there are no records to support the assumption. However, following her death, Donovan finds a bottle of medicine in her room.

Friday, September 7, Saturday, September 8th:

5:00 PM: Amelia Palmer again sees Annie in Dorset Street. Chapman is sober and Palmer asks her if she is going to Stratford (believed to be the territory where Annie plied her trade). Annie says she is too ill to do anything. Farmer left but returned a few minutes later only to find Chapman not having moved. It's no use my giving way," Annie says "I must pull myself together and go out and get some money or I shall have no lodgings."

11:30 PM: Annie returns to the lodging house and asks permission to go into the kitchen.

12:10 AM: Frederick Stevens, also a lodger at Crossingham's says he drank a pint of beer with Annie who was already slightly the worse for drink. He states that she did not leave the lodging house until 1:00 AM.

12:12 AM: William Stevens (a printer), another lodger, enters the kitchen and sees Chapman. She says that she has been to Vauxhall to see her sister, that she went to get some money and that her family had given her 5 pence. (If this is so, she spent it on drink.) Stevens sees her take a broken box of pills from her pocket. The box breaks and she takes a torn piece of envelope from the mantelpiece and places the pills in it. Chapman leaves the kitchen. Stevens thinks she has gone to bed.

It appears obvious that she did pick up medication at the casual ward. The lotion found in her room may have brought up there at this time. This would re-enforce Stevens' impression that she had gone to bed. She certainly shows every sign of intending to return to Crossingham's.

1:35 AM: Annie returns to the lodging house again. She is eating a baked potato. John Evans, the night watchman, has been sent to collect her bed money. She goes upstairs to see Donovan in his office. "I haven't sufficient money for my bed," she tells him, "but don't let it. I shall not be long before I'm in." Donovan chastises her, "You can find money for your beer and you can't find money for your bed." Annie is not dismayed. She steps out of the office and stands in the doorway for two or three minutes. "Never mind, Tim." she states, "I'll soon be back." And to Evans she says, "I won't be long, Brummy (his nickname). See that Tim keeps the bed for me." Her regular bed in the lodging house is number 29. Evans sees her leave and enter Little Paternoster Row going in the direction of Brushfield Street and then turn towards Spitalfields Market.

4:45 AM: Mr. John Richardson enters the backyard of 29 Hanbury St. on his way to work, and sits down on the steps to remove a piece of leather which was protruding from his boot. Although it was quite dark at the time, he was sitting no more than a yard away from where the head of Annie Chapman would have been had she already been killed. He later testified to have seen nothing of extraordinary nature.

5:30 AM: Elizabeth Long sees Chapman with a man, hard against the shutters of 29 Hanbury Street. they are talking. Long hears the man say "Will you?" and Annie replies "Yes." Long is certain of the time as she had heard the clock on the Black Eagle Brewery, Brick Lane, strike the half hour just as she had turned onto the street. The woman (Chapman) had her back towards Spitalfields Market and, thus, her face towards Long. The man had his back towards Long.

A few moments after the Long sighting, Albert Cadosch, a young carpenter living at 27 Hanbury Street walks into his back yard probably to use the outhouse. Passing the five foot tall wooden fence which separates his yard from that of number 29, he hears voices quite close. The only word he can make out is a woman saying "No!" He then heard something falling against the fence.

Mortuary photograph of Annie Chapman.

Annie's body was discovered a little before 6.00am by John Davis, a carman who lived on the third floor of No.29 with his family. After alerting James Green, James Kent and Henry Holland in Hanbury Street, Davis went to Commercial Street Police Station before returning to No.29.

Annie's Clothes and Possessions:

- Long black figured coat that came down to her knees.

- Black skirt

- Brown bodice

- Another bodice

- 2 petticoats

- A large pocket worn under the skirt and tied about the waist with strings (empty when found)

- Lace up boots

- Red and white striped woolen stockings

- Neckerchief, white with a wide red border (folded tri-corner and knotted at the front of her neck. she is wearing the scarf in this manner when she leaves Crossingham's)

- Had three recently acquired brass rings on her middle finger (missing after the murder)

- Scrap of muslin

- One small tooth comb

- One comb in a paper case

- Scrap of envelope she had taken form the mantelpiece of the kitchen containing two pills. It bears the seal of the Sussex Regiment. It is postal stamped "London, 28,Aug., 1888" inscribed is a partial address consisting of the letter M, the number 2 as if the beginning of an address and an S.

Dr. George Bagster Phillips describes the body of Annie Chapman as he saw it at 6:30 AM in the back yard of the house at 29 Hanbury Street. This is inquest testimony.

"The left arm was placed across the left breast. The legs were drawn up, the feet resting on the ground, and the knees turned outwards. The face was swollen and turned on the right side. The tongue protruded between the front teeth, but not beyond the lips. The tongue was evidently much swollen. The front teeth were perfect as far as the first molar, top and bottom and very fine teeth they were. The body was terribly mutilated...the stiffness of the limbs was not marked, but was evidently commencing. He noticed that the throat was dissevered deeply.; that the incision through the skin were jagged and reached right round the neck...On the wooden paling between the yard in question and the next, smears of blood, corresponding to where the head of the deceased lay, were to be seen. These were about 14 inches from the ground, and immediately above the part where the blood from the neck lay.

He should say that the instrument used at the throat and abdomen was the same. It must have been a very sharp knife with a thin narrow blade, and must have been at least 6 in. to 8 in. in length, probably longer. He should say that the injuries could not have been inflicted by a bayonet or a sword bayonet. They could have been done by such an instrument as a medical man used for post-mortem purposes, but the ordinary surgical cases might not contain such an instrument. Those used by the slaughtermen, well ground down, might have caused them. He thought the knives used by those in the leather trade would not be long enough in the blade. There were indications of anatomical knowledge...he should say that the deceased had been dead at least two hours, and probably more, when he first saw her; but it was right to mention that it was a fairly cool morning, and that the body would be more apt to cool rapidly from its having lost a great quantity of blood. There was no evidence...of a struggle having taken place. He was positive the deceased entered the yard alive...

A handkerchief was round the throat of the deceased when he saw it early in the morning. He should say it was not tied on after the throat was cut."

Report following the post mortem examination:

"He noticed the same protrusion of the tongue. There was a bruise over the right temple. On the upper eyelid there was a bruise, and there were two distinct bruises, each the size of a man's thumb, on the forepart of the top of the chest. The stiffness of the limbs was now well marked. There was a bruise over the middle part of the bone of the right hand. There was an old scar on the left of the frontal bone. The stiffness was more noticeable on the left side, especially in the fingers, which were partly closed. There was an abrasion over the ring finger, with distinct markings of a ring or rings. The throat had been severed as before described. the incisions into the skin indicated that they had been made from the left side of the neck. There were two distinct clean cuts on the left side of the spine. They were parallel with each other and separated by about half an inch. The muscular structures appeared as though an attempt had made to separate the bones of the neck. There were various other mutilations to the body, but he was of the opinion that they occurred subsequent to the death of the woman, and to the large escape of blood from the division of the neck.

The deceased was far advanced in disease of the lungs and membranes of the brain, but they had nothing to do with the cause of death. The stomach contained little food, but there was not any sign of fluid. There was no appearance of the deceased having taken alcohol, but there were signs of great deprivation and he should say she had been badly fed. He was convinced she had not taken any strong alcohol for some hours before her death. The injuries were certainly not self-inflicted. The bruises on the face were evidently recent, especially about the chin and side of the jaw, but the bruises in front of the chest and temple were of longer standing - probably of days. He was of the opinion that the person who cut the deceased throat took hold of her by the chin, and then commenced the incision from left to right. He thought it was highly probable that a person could call out, but with regard to an idea that she might have been gagged he could only point to the swollen face and the protruding tongue, both of which were signs of suffocation.

The abdomen had been entirely laid open: the intestines, severed from their mesenteric attachments, had been lifted out of the body and placed on the shoulder of the corpse; whilst from the pelvis, the uterus and its appendages with the upper portion of the vagina and the posterior two thirds of the bladder, had been entirely removed. No trace of these parts could be found and the incisions were cleanly cut, avoiding the rectum, and dividing the vagina low enough to avoid injury to the cervix uteri. Obviously the work was that of an expert- of one, at least, who had such knowledge of anatomical or pathological examinations as to be enabled to secure the pelvic organs with one sweep of the knife, which must therefore must have at least 5 or 6 inches in length, probably more. The appearance of the cuts confirmed him in the opinion that the instrument, like the one which divided the neck, had been of a very sharp character. The mode in which the knife had been used seemed to indicate great anatomical knowledge.

He thought he himself could not have performed all the injuries he described, even without a struggle, under a quarter of an hour. If he had down it in a deliberate way such as would fall to the duties of a surgeon it probably would have taken him the best part of an hour."

Funeral

Annie Chapman was buried on Friday, 14 September, 1888.

At 7:00am, a hearse, supplied by a Hanbury Street Undertaker, H. Smith, went to the Whitechapel Mortuary. Annie's body was placed in a black-draped elm coffin and was then driven to Harry Hawes, a Spitalfields Undertaker who arranged the funeral, at 19 Hunt Street.

At 9:00am, the hearse (without mourning coaches) took Annie's body to City of London Cemetery (Little Ilford) at Manor Park Cemetery, Sebert Road, Forest Gate, London, E12, where she was buried at (public) grave 78, square 148.

Annie's relatives, who paid for for the funeral, met the hearse at the cemetery, and, by request, kept the funeral a secret and were the only ones to attend.

Copy of Annie Chapman's death certificate.

The funeral of Annie Chapman took place early yesterday morning [14 Sep], the utmost secrecy having been observed, and none but the undertaker, police, and relatives of the deceased knew anything about the arrangements. Shortly after seven o'clock a hearse drew up outside the mortuary in Montague-street, and the body was quickly removed. At nine o'clock a start was made for Manor Park Cemetery. No coaches followed, as it was desired that public attention should not be attracted. Mr. Smith and other relatives met the body at the cemetery. The black-covered elm coffin bore the words "Annie Chapman, died Sept. 8, 1888, aged 48 years." (The Daily Telegraph, September 15 1888, page 3)

Chapman's grave no longer exists; it has since been buried over.

Death Certificate

Death Certificate: No. 281, registered 20 September, 1888 (HC 084466). The certificate does not list the inquest from 13 September.